Editors’ Note: Pray our eternal thanks to Paul Graham Raven for this thoughtful epic which he wrote as his DP swansong, instead of working on an actual Book-For-Publication. Pretty foolish of him, but we love him to bits anyway. Also it’s rather brilliant. Godspeed, you mad lugubrious bastard (nb: lugubrious means ‘wordy’ okay?).

Over the last five years or so, I’ve come to the conclusion that music doesn’t matter like it used to, and that it doesn’t matter that it doesn’t matter.

The image that drove it home was a poster for some student shin-dig, an “iPod disco”—a night out where everyone goes to da club with their own music player, and dances to their own beat as heard on their headphones. How utterly neoliberal is that? You couldn’t make a better metaphor for individualist consumerism if you tried. Music as wallpaper, a domesticated and utterly internal experience, rather than the communal channel of experience and story that even two hours of cheesy hard house in a backstreet Sheffield flea-pit manages to convey… despite seeming to privilege how much music matters to the attendee, the iPod disco does exactly the opposite: it privileges how much the attendee matters to themselves. And I consider this to be emblematic of a more general (if less extreme) decline in the importance of music as a central plank of youth cultural identity, at least in the UK.

On one level, that sounds ridiculous: “You’re saying music doesn’t matter anymore? Now, with music more ubiquitous, accessible and diverse than it ever has been before in the history of humankind? How could it not matter?!”

And sure, music still matters; it’s a crucial layer of cultural topography. But it’s not the dominant channel of subcultural ideas any more; it’s just one channel among many, all of which are busily being subsumed into the metachannel, otherwise known as these here internets upon which I am writing to you.

But before the internet, music was the internet.

Allow me to explain.

#

First of all, you need to think of “the recording industry” as a system, as a medium; step back from the actual components of the machine—the radio stations, record companies, recording studios and record stores—and think purely in terms of function. Alongside magazines, pop records were the first medium explicitly marketed at the then newly-minted demographic of The Teenager; recordings had been sold before then, of course, but they were a less ephemeral sort of cultural product; albums that curated serious art by serious artists were marketed to collectors and connoisseurs. The 7-inch single was a way to make a fast buck out of the fleeting tastes of these strange new Teenaged creatures.

As history shows, this market expanded incredibly fast, and sideband channels of marketing and publicity sprung up around it; the business learned how to shape the tastes of its audience by carefully curating the novelty to which it was exposed. At the same time, the business became increasingly infrastructural as it expanded. This is unavoidable, because it is functionally similar to a telecoms company; it’s in the business of delivering messages to paying subscribers, and once the volume of messages becomes significant, it’s all you can do to keep on top of the logistics. Worrying about exactly which messages the subscribers want becomes mere detail; so long as the demand is there, you’re happily making bank, but you’ve gotta keep those pipes flowing. A corporation is an economic entity, remember; it doesn’t have (or need) the capacity to care what it’s selling, so long as it’s selling it and making money.

But the machine doesn’t run without that demand, so the infrastructure had to be fed with novelty by the “creative” side of the business, the managers and A&R people, promoters and pluggers and hustlers of every stripe. Meanwhile, the first generations of pop listeners reached an age where they’d started their own bands; these are the first bands to have grown up believing that there could be music aimed specifically at them, at young people in their world. No surprise, then, that when they picked up their instruments they found they had things they wanted to say—things that no one would let them say anywhere else, on the radio, on television, in the newspapers. It was a generational backchannel, if you like; a peer-to-peer medium where youth could speak to youth.

At no time in your life are you ever more hungry for new stories and new ideas than when you’re a teenager; outside of books and magazines (the latter of which were increasingly aligned with the music business anyway), music was the most likely place you’d hear the shibboleths of your generation spoken aloud. Rebellion, lust, desire, frustration, and the sheer shattering thrill and terror of being young and alive—to know someone else felt the same must have been an incredible liberation after the bland suits’n’boots orgman conformity of the post-war years. And while there was some money to be made from peddling saccharine conformity, the market turned out to be hungry for the forbidden topics—which was just fine for the recording industry: The forbidden could flow just as smoothly through the pipes as the wholesome. Hell, sometimes the forbidden flowed better, especially when someone outside the system tried to impede it; then as now, nothing heightens demand like a banning.

So maybe you can see what I mean now if I say that the early pop recording industry was like a very asymmetrical internet for contemporary youths, where a limited few (by the good graces of the infrastructural side of the business, who could make a buck from it) got the chance to publish new ideas and stories, and the majority could access and (to a limited extent) share those messages around. This is the era of the newly electrified Dylan, the early Beatles and Stones, ‘the British invasion’, all that stuff.

The system is biased against certain sorts of message, of course, and in some cases very strongly; it’s far from an ideologically flat marketplace. But nonetheless, there’s more levity here than elsewhere, and the very narrowness of this much-desired channel makes it very lucrative indeed, especially as the wider world of business begins to recognise the power of the Teenaged pound, and the utility of an established hot-line to its most active and willing consumers. However, with a firm hold over access to the means of (re)production, the industry could maintain a broadly conservative control over the general tone: when the pipes are flowing fast, you want to avoid riling the regulators excessively. Only trouble being, the more successful your artists become, the more likely they seem to be to start cocking a snook at the establishment… and you don’t want to entirely stamp that out, because it’s so bloody lucrative, eh wot?

Around this time, the capabilities of recording equipment and studios were also expanding rapidly, and the costs of getting records out into the market were falling, lowering the barriers to new contenders for the still-small but ever-expanding roster of artists with access to the medium, plus new, smaller players among the record companies, piggybacking on the now predominantly-infrastructural distribution side of the business. Music mutated its way through myriad forms, but the real Cambrian explosions came with the arrival, from the late 70s onwards, of affordable electronic instruments and home recording equipment, and the arrival of consumer-grade home duplication systems—the miniMoog and the cassette recorder, in other words—which had a significant part to play in the emergence of (post-)punk and electronica, and paved the way for the synthesiser-drenched 80s, the rave explosion, 90s grunge and alt-rock and everything else.

Pepsi today announced an exclusive global partnership with the Estate of Michael Jackson as part of its new “Live for Now” campaign/

But it’s the ability to record and duplicate at home that’s important if we’re thinking about music as a medium, because this is the point where the traditionally-asymmetrical access to the industry starts to trend toward the symmetrical; all of a sudden, true peer-to-peer transmission is possible (albeit slowly, with considerable loss of quality, and at not insignificant opportunity cost), as is cheaply obtaining and sharing the messages of “official” artists without recourse to the official channels.

I reckon this technological shift has as much to do with the expansion of forms and styles of the late 70s and beyond as the sociopolitics of the time; it’s not just that there was so much more experimentation going on, it’s also that the experimenters could create their works and disseminate them cheaply, as well as becoming able to bypass the gatekeepers of the industry and connect directly with audiences.

(Does that rhetoric sound familiar, at all?)

So the industry lost some of its control, but ultimately gained from yet more growth in the overall market; so what if there were more bad messages in the pipe, so long as there were more messages? And while it got cheaper and easier for consumers to record and duplicate, the business still had the lion’s share of the power when it came to high bandwidth distribution, which allowed it to co-opt and absorb the smaller channels, once they reached a point where they need to scale their business up and onto the established infrastructures to keep their margins viable.

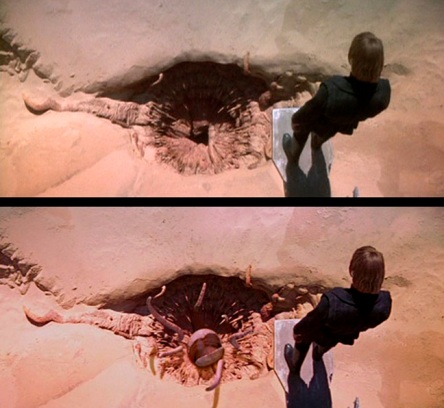

Sure, there’s mail-order 7-inch-single clubs from marginal labels run out of someone’s shed, pirate radio stations, but that’s all little-league shit; if you want the big reach, you need the big pipes, and if you wanna use their pipes, you gotta deal with the big boys… and when you do, they’ll take up your niche and commercialise it quicker than you can say “UK grime was once a viable and genuinely interesting music scene”. It happened to punk, to synth-pop, New Romo, C90 indie, to every successive sub-wave of the rave explosion, to grunge, Britpop, everything; as soon as a new message or idea hits the infrastructure, it’s everywhere, it’s ubiquitous, it’s over. This is why we talk about “selling out”, but it happens at a much higher level than individual artists, and it’s a two-way process. The infrastructural core of the business has to suck in novelty from the outer edges in order to fuel the machine and keep the pipes flowing; it’s like a black hole, in a way. Or maybe a sarlacc pit.

But the bigger the black hole, the greater the surface area of its event horizon, meaning the marginal ecosystem of independent artists clinging onto the edges of the infrastructure; so many voices out there, so many new stories! I remember being a teenager in the early 90s, with music being the only way I could gain access to any view of the world that wasn’t seen from what I now recognise as a white British middle-class perspective; it was the only place I could hear about the sort of politics that mattered to me, the only place I heard the truths that elsewhere went unspoken, the only place where lives that felt like my own were narrated. (Well, there were novels, too, but who reads those anymore, amiritez?) It was a crazy time—though I suppose the period during which you become an adult always looks like that, whenever you’re born.

The 90s also threw up the internet, the metamedium which would go on to subsume all other mediums, but it would be a long time before enough people had it that anyone could guess what it’d be good for. So it kinda bubbled along as a rather obscure channel-of-subcultural-backchannels until bandwidth and baud rates and processor speeds got to the point where Napster could happen.

At which point all bets were off.

As we now know, thanks to the 2002 invention of hindsight, the recording industry either hadn’t seen this coming or had chosen to ignore it; indeed, there are big sections of the industry only now, 15 years later, slipping out of the denial stage and adapting to the new landscape. But everything changed, again, once the opportunity cost for finding and duplicating a song and sharing it with someone became effectively zero; suddenly those messages were multiplying like Gremlins in a swimming pool, pouring through a whole new set of pipes, under a whole new set of rules, beyond reach or control. Owning the recording industry’s manufacturing and distribution infrastructure was suddenly an expensive liability… and the nature of the new distro channels was that it made your product laughably easy to duplicate infinitely, with no significant loss in quality.

I think this is where our relationship with music really began to pivot, because suddenly access to the music you wanted needn’t be a matter of expense: you could just have it, whether streamed or torrented or ripped or whatever. Music – not just contemporary music, mind, but as time passed, the entire corpus of recorded music—everything that’s still capable of playback and redigitisation—became a resource, a commodity, an ocean of sound that our access to the internet allowed us to draw from effortlessly, without friction, and over a wider selection than was even conceivable beforehand. Yes, you still choose your music—but you choose it lightly, spoiled by choice. It’s not a hoarded pocket-money purchase, a long-anticipated mail-order CD of some obscure album that your local HMV didn’t even have on its database, or some long-forgotten b-side that you’ve scoured an endless string of backstreet record shops to find; it’s a coat plucked on a whim from an infinite coat-rack. What do you want to wear today?

And hey, why not—this is not a bad thing. It’s just the way things are… and as many bad things as there are about the world and about the internet, I don’t think this is one of them. Nor is this one of those “OMFG music is DEAD these modern bands SUCK and you should all get the hell off my LAWN” sorta essays, either; music’s definitely not dead, it’s alive and crawling like kudzu, soundtracking our workdays as much as our playdays, thanks to teeny-tiny technology and better batteries. Music and musicians aren’t disappearing anytime soon; sure, it may be harder to secure the sort of mid-list careers that album bands could have in the 70s, 80s and 90s, but that’s because the labels can’t play the old “throw shit at the wall and see what sticks” approach to A&R any more; they don’t have the monopoly over distribution or promotional channels any more, so they can’t stack the deck so easily in their own favour. They were gamblers in the golden age, taking a chance on dozens of bands in the hope that one would be the new Beatles, Led Zep, whoever; it was a poor method, but it was the best one they had. (And if the rock biographies are to be believed, it could be quite a fun process, provided you didn’t let it kill you.)

But don’t believe the hype about the music industry being in decline. Far from it; it’s just abandoned the old infrastructural business model and merged with the TV and Hollywood conglomerates, getting into the “content” game, which is a game of stories within stories within stories, of which music is only one type among many. But selling music itself is a dead scene for anyone operating outside the Long Tail; as soon as something’s in sufficient demand, piracy takes care of the supply problem for you, and leaves you out of pocket. You only avoid this by being obscure… and if you’re obscure, you’re not expecting to make any money from selling records, anyway, except as exactly the sort of connoisseur’s collection-piece that recorded music first got sold as: high-weight vinyl albums of obscure Williamsburg drone-pop quartets. These are artefacts, treasures; their value does not lie purely in the music that they encode. This is the last bastion of music really mattering to people like it used to: obsession, the expense of time and money. Try rewatching High Fidelity; it was always a little satirical, but now it looks like a send-up of the doomed relics of a by-gone era, twisted man-children angsting over their grown-up Pokémon collections. Defining yourself by the physical albums you own – how limited an idea that seems now! (If only because, well, shit – who can afford a spare room for their vinyl now the bedroom tax is in, eh?)

You want the proof that music doesn’t matter? Look at the charts. Sure, they were always topped-off with obvious pop puppets, but now even they are carefully groomed and manufactured—in public, and at great length, as part and parcel of the whole spectacle—long before they ever release any actual tunes one can buy. And when they are released, they’re a sideshow, a vestigial legacy-mechanism by which you get the act to chart, and thus to be talked about more. The money in pop music nowadays is all in using it as the honey coating on bigger and more easily-monetised media spectacles like television or cinema, or as a demographic shorthand in advertising material. Simon Cowell’s exploitative franchises have made him many fortunes, but hardly any of that came from record sales; it comes from the ad slots that appear around his programs, from the licenses to reuse his formulae in other territories; he’s not selling music, he’s selling the idea of selling… Music’s just the scent of fresh-baked bread piped out from the front door of his underground-railway-themed sandwich shop, so to speak; its job is to get you in through the door.

(This, in fact, is not that far away from the old Tin Pan Alley model of the early 60s, or Pete Waterman’s “hit factory” model of the 80s; the only difference is that now it’s easier to monetise the artist selection and development process than the resulting musical product.)

However, there’s masses of other stuff going on, little sub-sub-genres and scenes of all sorts popping up all over, outside the dominant channels of promotion; how can I say music doesn’t matter when more people are making it or going to listen to it than ever before? Yet at the same time, there’s a sense that everything’s been done before, everything’s been said already. Caught in the atemporality of postmodernism’s end-game, all that’s left to us is quotation, pastiche, mash-ups and covers and remixes. The possibility of newness is nowhere to be seen.

#

To repeat: music still matters, but it matters in the abstract, as one aspect of the sensorial tapestry that is our cultural lives. It’s not a lifeline like it once was; there are other channels now where youth can speak to itself, even if they’re increasingly clogged with the detritus of capital and commerce. It doesn’t have to carry all the weight of our hopes and fears any more; nor our politics, our dreams of futurity. There are other ways to make the world hear us, and while they may not be much more effective, they’re surely no less so.

And maybe I’m wrong, and a few miles away there’s some urgent new musical subculture coalescing in some grotty little venue, the first true Next Big Thing of the Internet Era, set to blow people’s minds and give them a star to steer by. I wouldn’t be sad to see it; hell, I’ve spent years watching hungrily for it. Put me out of my misery, y’know?

But ultimately it doesn’t matter that music doesn’t matter so much, because the internet subsumed the recording industry, absorbed that systemic function into itself, perfected it, balanced the asymmetry (a bit). Oh, it’s no utopia, no matter what Silicon Valley and its boosters may claim to the contrary, and there’s a lot of work to be done before we’ve shaped the internet into something that serves all of us, instead of just a few. But even so, the messages are still getting through, whatever the platform, whatever the medium… and it’s never been easier to send your own message back out there and see what happens.

And that’s what always mattered about music in the first place.

To follow Paul’s future exploits, check out his personal blog at www.velcro-city.co.uk.